The Tech Behind Swarm

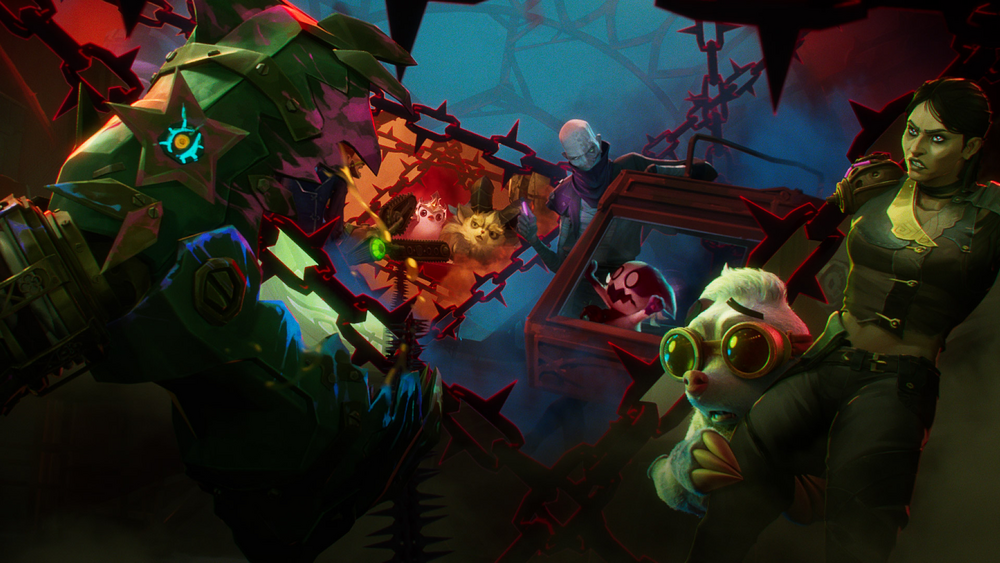

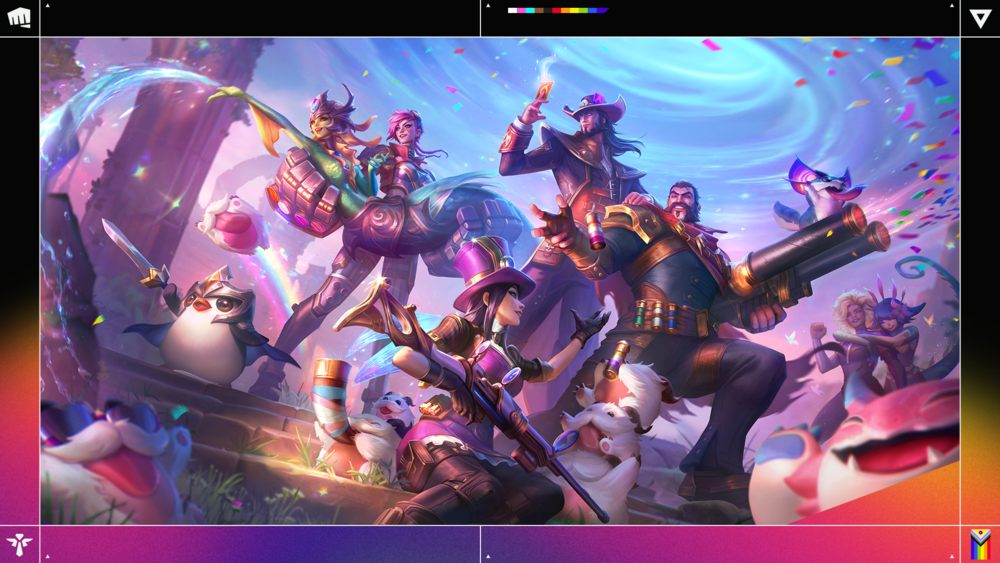

This time last year, alien Primordians had invaded Final City. The Anima Squad was the only hope to fend them off. Players around the world sent trains flying, bullets in circles, and mines all over the map as they took down wave after wave in Swarm.

When Swarm debuted, it was a different game mode than anything we’d done in the past. The bullet-heaven style mode required WASD movement, a toggle between manual and auto aim, and new abilities. Behind the scenes, it also required our engineers to solve a variety of technical problems that weren’t quite as player facing.

That’s what we’re here to talk about today. If you’re new to the Riot Games Tech Blog, this is where we turn the keys over to the engineers behind the game to talk about their work and some of the problems they solved over the course of a project.

We go pretty deep into the tech here, so these articles are geared for fellow engineers, students interested in pursuing a career in tech fields, or players who are particularly interested in the challenges many Rioters work on that aren’t as visible in the day-to-day of the game.

We’ve got a triple feature for you all today. To start, Nancy “Riot Nancyyy” Iskander, the Tech Lead on Swarm, will take you through the challenges of making Swarm feel like an actual swarm with hundreds of minions on the map at once.

Next, Andrew “Riot H28 G EVO” Hilvers, the Senior Engineering Manager on Modes, will dive into the impact on the servers with a look at how modes impact server usage, the difference between PvP and PvE, and how the team worked to keep Swarm running smoothly.

And finally, Taylor “Riot Regex” Young, a Software Engineer on Swarm, will walk you through Swarm’s progression system and how parts from other systems were used to model the roguelike system’s challenges, scaling, and unique gameplay mechanics.

We’ll start with Riot Nancyyy’s portion, but if you’re interested in just one of the other two, use the nav links below and you’ll jump straight there:

Making Swarm a Swarm

Hi everyone, I’m Riot Nancyyy, the Tech Lead on Swarm. In this article, I’ll be sharing some behind-the-scenes work by the Swarm engineering team, with a focus on in-game optimization.

League of Legends is a server-authoritative multiplayer game, hosted on dedicated servers, a paradigm that doesn’t lend itself very well to a bullet-heaven mode like Swarm. The engineering challenge was twofold: first, drastically increase the number of minions that could be active at once in comparison to other modes, and second, reduce the server cost to offset the lower player count.

Our approach was simple: spawn hundreds of minions, identify the biggest performance bottleneck, optimize, rinse and repeat!

Swarm Minions

Our first consideration was how we would implement complex optimizations in the same codebase that’s driving live game modes like Summoner’s Rift, TFT, ARAM, and other rotating game modes, without handicapping ourselves with extensive regression testing at every step.

All League modes heavily employ the minion class—lane and jungle minions, TFT units, pets, objects like Teemo shrooms, and even some AoE effects all have the same internal representation. That’s why even subtle changes to this class could have unintended ripple effects across all modes.

The trade-off we were considering with the choice of Swarm minion representation was whether we wanted to stick to the minion object with all of its features and added baggage, or to start anew with a lightweight object that we could more easily optimize. Given our development timeline, we needed to unblock design iteration on the mode as soon as possible, so we went with a compromise, where we added a new leaf to the object hierarchy as a sibling to the Minion object. The parent class gave us enough features to unblock iteration, while allowing us to optimize several features independently of live modes.

So, what are the practical differences between League and Swarm minions? Swarm minions don’t allocate any resources to classic League features like lanes, jungle camps, or vision. They also replicate less data to the client and do so more selectively. The biggest difference is how Champions interact with them, but more on that later!

Pathfinding & Movement

With the switch to lighter-weight minions, we could spawn hundreds of attackable, visible, animated minions while maintaining good server and client performance—at least, until those minions started moving.

Our early tests revealed a significant challenge: pathfinding was scaling almost quadratically with the number of minions. League of Legends uses A* pathfinding, which remains the gold standard for general-purpose pathfinding in gaming. However, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution—especially when swarms of minions are involved. For those unfamiliar, A* is an agent-based algorithm where we find a path from a specific source to a specific target, where paths that have the shortest lengths are explored first. Along each path explored, collisions are checked with other minions. Therefore, we have to find a path for each individual minion, and each minion’s pathfinding is made more complex the more minions there are to collide with, hence the worse-than-linear scaling.

Aside from performance, we encountered issues like overlap and clumping, which not only reduced visual clarity but also increased overdraw, which negatively impacted client performance. On top of that, we saw scattered movement in certain areas where minions failed to realize their paths were blocked, causing even more chaos.

With the time frame we had to develop Swarm, completely overhauling pathfinding wasn’t exactly something we were eager to do. We tried tweaking existing parameters—reducing collision radii, lowering pathfinding accuracy, and capping path complexity so minions would “give up” sooner. While these adjustments did improve performance, it quickly became clear that we were hitting diminishing returns. Performance improvements came at the cost of responsiveness and accuracy. Worse yet, this left us with no breathing room for any additional server-heavy features—which, in retrospect, we absolutely needed.

Global Pathfinding

The solution was to replace agent-based pathfinding with global pathfinding. Global pathfinding is an approach where a single pathfinding computation determines the optimal routes for multiple units across a shared environment, towards common goal positions. As you might expect, there’s a threshold number of minions after which the global computation becomes more cost-effective, and that was exactly the case for Swarm.

Swarm’s global pathfinding algorithm is a version of Dijkstra’s maps (or Flowfield pathfinding) customized to fit our needs. The algorithm starts by assigning a cost of zero to each target location (i.e. Champions) and then propagates costs outward, incrementing the cost with each step. When minions need to move, they simply follow the path of decreasing costs. Minions apply a collision “stamp” as they move, depending on their size, modifying the flow around them.

While this is sufficient for navigation, each minion also needs to know which champion they’re targeting for gameplay purposes. To achieve this, each cell tracks which goal positions contribute to its current cost. This is stored as a bitfield of goal indices, where each bit represents a champion.

Keeping track of which goals are contributing to a cell’s cost unlocked a new optimization: if a cell's lowest cost is derived from a static goal (i.e. a goal that hasn’t moved to a new cell since the last frame), it can be updated by a dynamic goal (i.e. one that has moved) only if it gives it a lower cost. In other words, a cell’s cost is only updated (and propagated to neighbors) if it receives a lower cost from any goal, or a higher cost from all the goals it’s tracking.

While this might not sound significant since players are not static, non-zero cell width means that not all players will cross into new cells each frame. This optimization allows us to skip recalculating large portions of the map each frame!

Movement

We’ve discussed how Swarm does pathfinding differently, but we also made changes to how minions move along those paths. In both classic League and Swarm, each unit receives its path in the form of waypoints. Both client and server smoothly interpolate the unit’s position along the path in a deterministic way.

In classic League, there are additional sophisticated calculations on the client to give the illusion that a unit is slowing down near the end of its path. Because Swarm minions move cell-by-cell, we actually don’t want their apparent speeds to fluctuate between cells. While this was too subtle to be an issue in itself, when stacked over multiple cells, these negligible modifications in speed caused an obvious desync between client and server.

We therefore replaced the movement driver with a simplified version that solved desync bugs, with the added benefit of improved client performance for large numbers of minions!

Pathfinding and Movement Result

With these optimizations, pathfinding and movement went from being one of the worst performance bottlenecks to one of the most scalable components of the mode. Global pathfinding isn’t affected by the number of minions, while movement scales in a well-behaved linear fashion. In addition, the end result is smoother and less chaotic.

Data-Driven Waves

We’re now able to spawn a large number of minions that can target and follow Champions all over the map. The next challenge was how to give designers flexibility to author all the different waves while maintaining performance.

The League of Legends Engine has a C++ layer and a scripting layer. C++ is used to implement core gameplay and features that require a high degree of efficiency (e.g., pathfinding), while script is used for more high-level gameplay that requires fast iteration and flexibility (e.g., a specific spell).

Given the high turnover rate of minions in Swarm and all the calculations and processing involved in spawning and despawning each one, we wanted wave spawning to be as efficient as possible. To that end, we created data-driven waves that are handled in C++ and authored through data in editor, rather than script.

In data, designers control when waves spawn or despawn, which characters are in each wave, how many minions are spawned, at what frequency, where, and in what shape… the list goes on! Most of these variables can be scaled by number of players and difficulty level.

Buff Batching

At this point, we have waves of primordians that are spawned according to wave data. Champions can attack these simple code-driven minions, but they cannot apply custom effects on them, such as AoE stuns and damage over time.

All of these effects are typically applied through scripts called “buffs.” These buffs are the primary tools designers use to implement gameplay mechanics. Unfortunately, buffs were also the single most performance-draining aspect of the early prototype, presenting a notable scaling challenge. So, what do we do when a repetitive task starts to strain performance? Enter batching!

The concept of buff batching is straightforward: rather than applying a buff to each individual minion, the buff is applied to a group of minions simultaneously. By batching the buff, we significantly reduce the overhead associated with creating, maintaining, and destroying countless buff instances for each affected minion. The relationship between minions and batches is many to many, where each minion can be a member of multiple batches, and each batch contains multiple minions. Each batch is represented by a set of reusable proxies, each carrying the buff associated with the batch.

The primary use case for batch buffs is applying champion abilities and weapon effects onto a group of minions. For instance, consider an ability like Leona's ult, where a single buff applies a timed AoE stun and damage over time to multiple targets.

Another use case is controlling the minions themselves. As I mentioned earlier, most minions in Swarm cannot carry buffs, except bosses and mini-bosses. But what about those in-between cases, like elite minions, where we need to spawn a large number of them, keep the wave performant, but with a bit of extra flair? In those cases, a batch buff is added to the wave data as an optional behavior, allowing designers more control over these minions while still keeping buffs in check.

I believe this is the first time in League history that we’ve had buffless minions that cannot be directly controlled through script. Modifying the way the game has always been scripted was nerve-wracking, but I have to give it to the Swarm designers who quickly adopted this style of scripting and still produced gameplay that feels authentic to League!

Client Optimization

Even after all the optimizations we talked about, the game still did not feel performant. This was largely a client problem, due to the crazy amount of things on screen all at once. Despite our server capacity metrics being within target, there were still moments when we were worried that we would have to cut back on the fun to make the game playable.

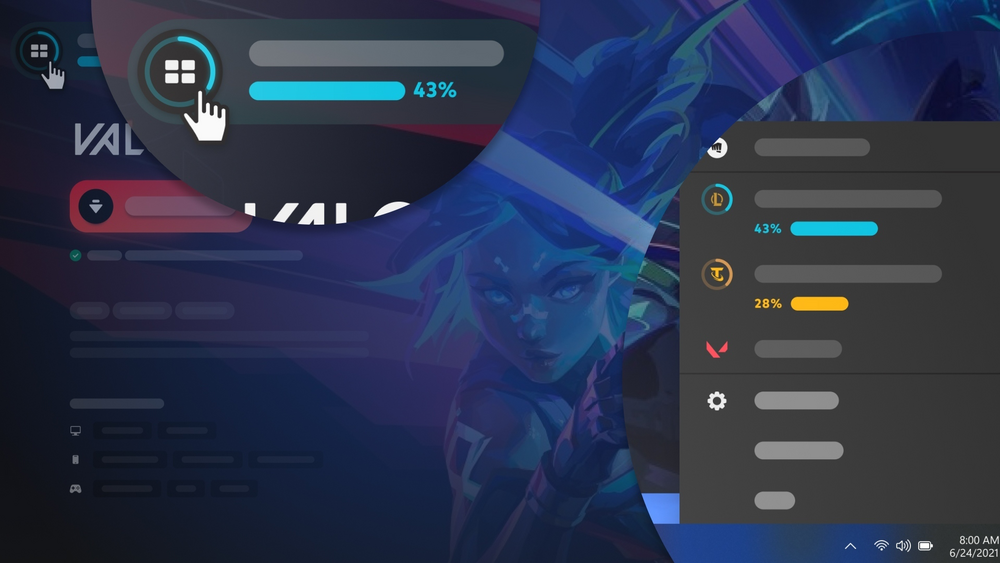

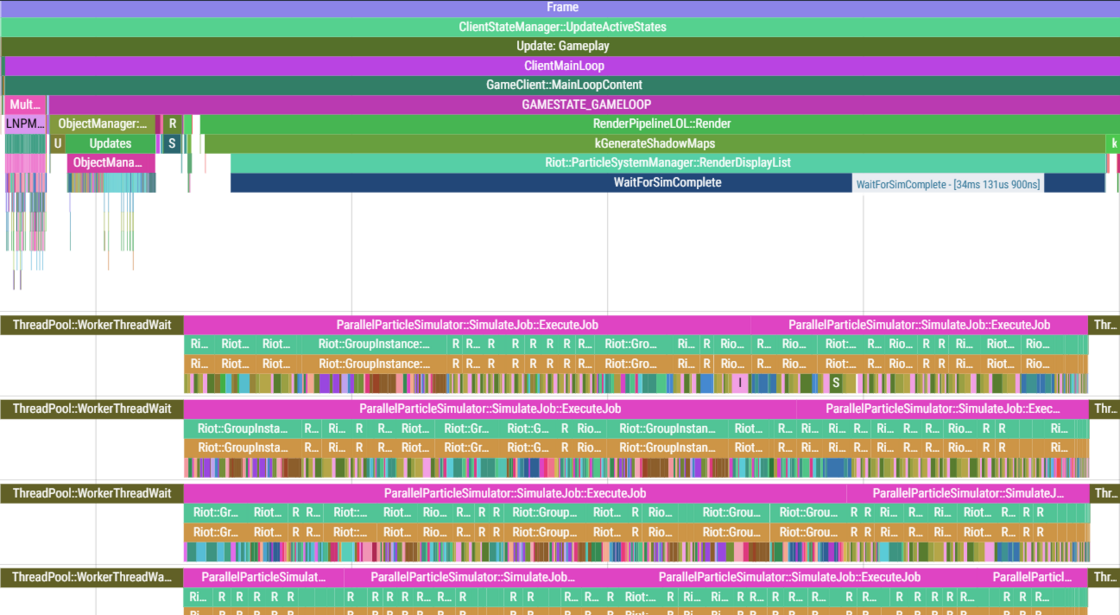

Here’s what a typical frame on the client used to look like:

Let’s break this down. We can see that there are multiple threads, doing primarily three things: object updates, rendering, and particle simulations. The main thread is where object updates (e.g., minion movement) happen, followed by rendering. Meanwhile, several helper threads are running particle simulations in parallel.

Despite a massive degree of parallelization, it was clear that particle simulations were the bottleneck. Because they were happening in parallel, further optimizations to object updates were likely to result in little to no gain.

We collaborated with the League of Legends engine team to understand how this works in more detail, which was the key to unlocking significant gains in performance. Particles are sorted by render pass, so particles that render later can continue to simulate in parallel until later in the frame. Conversely, anything in the first render pass—such as VFX shadows and ground particles—need to be fully simulated before the render process can start.

The VFX team took that information and optimized the most crucial particles, and with that, they solved our last performance blocker! Huge shoutout to the Swarm art team!

Conclusion

Swarm shipped with a limit of around 550 minions active at once. We have checks and balances in place to keep this number stable, but we’ve seen it spike to nearly 1,000 in some games.

Adding hundreds of minions to the game while simultaneously implementing a new game genre in our existing server-authoritative architecture was a huge technical challenge that took a high degree of collaboration across disciplines. In engineering, we had to rethink core parts of the game, like pathfinding and buffs. Designers adopted new scripting workflows and collaborated with us closely to ensure that everything we reimagined still felt true to League. Artists optimized hundreds of particles, literally. And production managed to work with the ambiguities inherent to open-ended problems like optimization, which, as anyone in software knows, is never truly done.

Thank you for allowing me to share a glimpse of the work that went into creating this mode. There’s so much more to explore (and optimize), and we’re excited to continue pushing the limits.

Now I’ll pass it on to Riot H28 G EVO to talk servers.

Swarm’s Smooth Servers

Hey everyone, Riot H28 G EVO here! I’m the Senior Engineering Manager on Modes, and I’m diving into how we approached game server capacity planning for Swarm. Swarm was an ambitious project, and there were plenty of doubts about whether we could pull it off. Like many online games, Swarm relies heavily on cloud servers to handle most of the game logic.

I’ll walk you through the challenges we faced with hosting game servers worldwide, how we solved (or struggled with) those issues, and how this experience has shaped our team’s approach to building future game modes.

Potential for Disaster

Server capacity planning is often a thankless job. When everything runs smoothly, hardly anyone notices, but when things go wrong, it can derail an entire project. From the outset, we knew that supporting League’s large playerbase, combined with Swarm’s unique gameplay, would present a massive technical challenge.

Perfect Storm of Constraints

When it comes to League of Legends’ game modes, Swarm is a bit of a unicorn:

It is a PvE experience with a large number of enemies

It supports co-op and single-player

Its combat is not MOBA style

Valid games can last anywhere from 30 minutes to 30 seconds

These unique attributes led to a new set of constraints on top of the common game mode constraints:

Core Tech: Even though Swarm is PvE and at times single player, we were still working within League’s engine and code base. The majority of our foundational tech assumes that modes are PvP, with server authoritative gameplay. For Swarm, this meant that the majority of the game logic still ran on the game server, which had the potential to balloon server costs due to its bullet heaven style of gameplay.

- Cost: Initial estimates (we will talk about how we got those in a bit) showed the cost to run Swarm to be ~2.5x the cost compared to the same amount of players playing Summoners Rift.

- Logistics: Even if we got that 2.5x dollar amount approved, we would have to work with our cloud hosting partners to see if we could even get that many servers, databases, network bandwidth, etc., allocated in time for our use.

- Downstream Services Impact: Assuming we could get the games themselves hosted, each time a game ends, ~50 backend services need to process that end of game data. For Swarm we estimated a ~5x increase in the amount of game ends compared to the same amount of players playing Summoners Rift, meaning those downstream services could also be heavily impacted.

Forecasting

Being able to accurately forecast your capacity needs is something that can make or break your release. Our approach was to use the wealth of data we had from our live game modes, and recent releases like Arena, to come up with what proved to be a very accurate projection.

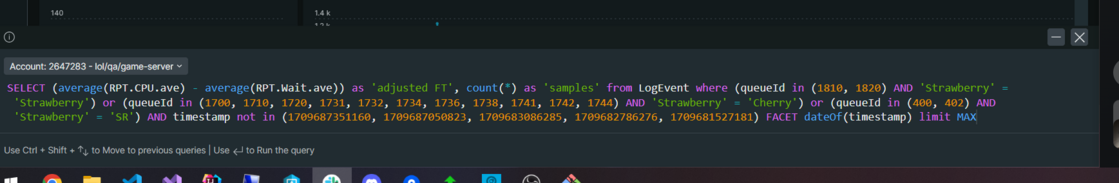

The hard to read, and maybe hard to understand :D, formula I created was as follows:

<Game Cost (CPU/Bandwidth/Etc) % Compared to SR> / <Average Player Count % Compared to SR> * <Share of Game Hours by Mode %> + (1 -<Share of Game Hours by Mode %>)

The key was our ability to take what was unique about Swarm and compare that to known aspects of Summoners Rift.

To break down the formula:

Game Cost: Depending on what you were evaluating, you would calculate how much an average game of Swarm compared in relative cost to an average game of Summoners Rift.

For example, Swarm was first measured in February 2024 to have a relative CPU cost 80% that of SR (or 20% cheaper to run).

Average Player Count: This represents the average number of human players per game. Since it’s a 1-1 game server count to game count for League, the standard rule is that the more players in a game the cheaper the game mode is to run.

Our projection early on was that in the worst-case performance we would see ~1.5 players per game.

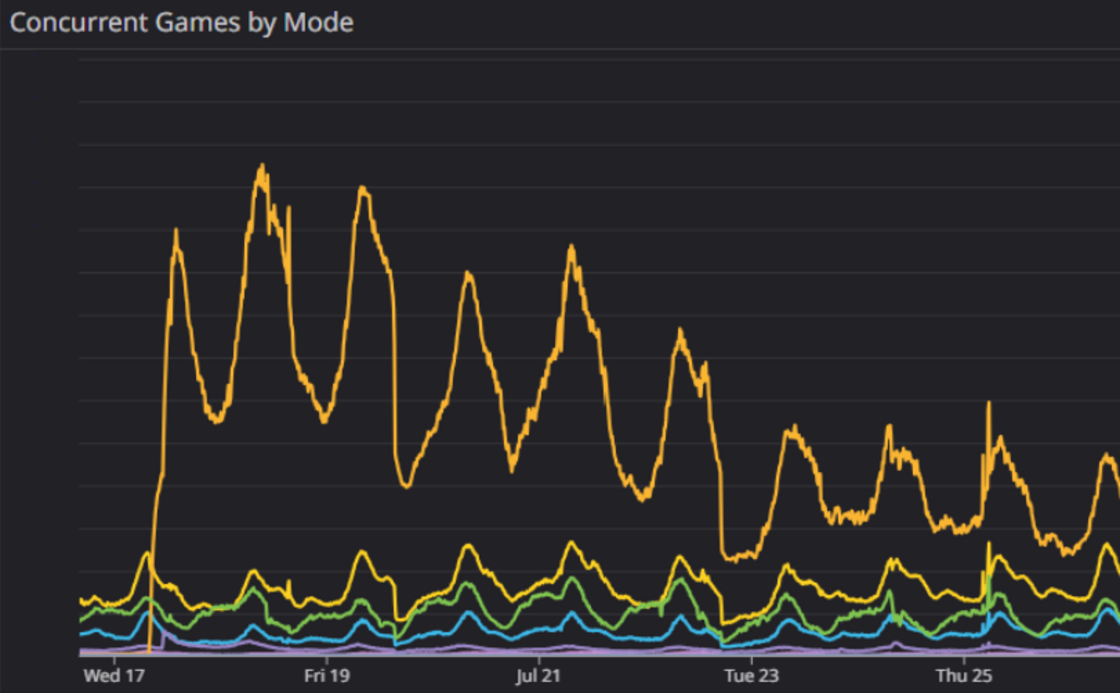

Share of Game Hours by Mode: This is arguably the most important projection for performance and the hardest one to get right. We looked at previous mode releases, like Arena, and used that to try to project what the max engagement could realistically be. It's important for capacity planning to try and figure out the highest realistic numbers, since this is when your capacity will be stressed the most.

This is represented as a % from 0-100 tracking what percentage of game hours during a time window are players in Swarm vs. all other League modes.

It should also be noted that we typically see the highest percentage over the first 48 hours of a mode's release, so this is roughly the time frame we use for this calculation.

After calculating all of these variables, you are left with a % of scaling needed relative to our steady state without the mode active.

For Swarm, our first projections done in February 2024 showed:

Game server CPU scaling = 251.67% or scaling up by ~2.5x.

Game end backend services scaling = 490.10% or scaling up by ~5x.

Game bandwidth scaling = 90% or no scaling needed. More on this later.

These were the numbers engineering took to production for budget approval, and what was initially approved, which ultimately helped the project get the final green light it needed.

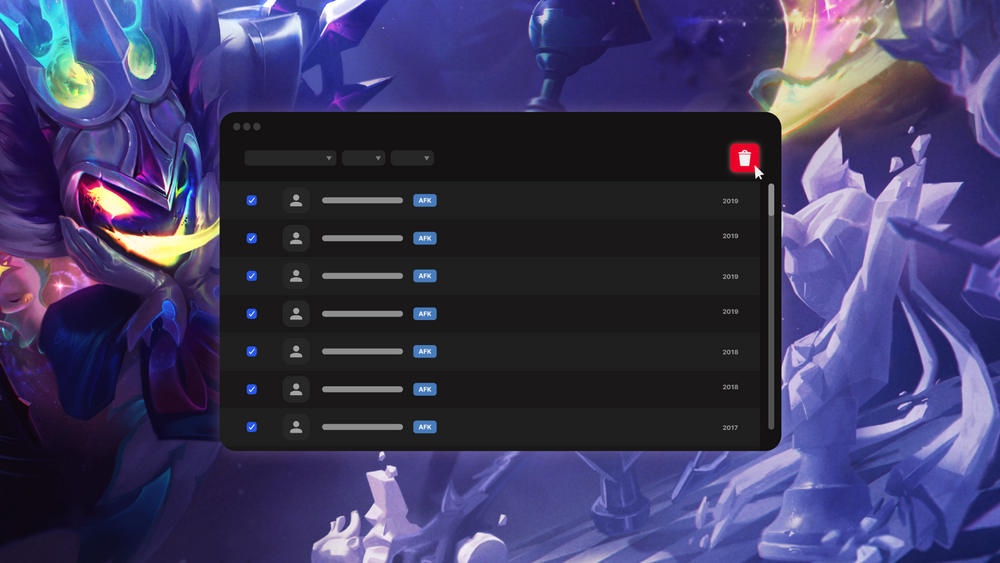

Monitoring Patterns

Initial forecasts are crucial, but with constant changes, having a way to easily monitor and adapt to those changes was key to Swarm's success. League has always collected a wealth of performance data, but where we’ve stumbled in the past on the modes team was in how we used, or didn’t use, that data. Typically, we’d only examine small samples of high-level data until we hit PBE, and then we’d spend a few weeks optimizing for release, and that was usually the extent of it.

With Swarm, we knew that would not be enough, so we set up a brand new modes process to help us monitor our performance throughout development:

Enabling Internal Data Collection: We worked with our engine team to enable the collection of every piece of performance data we could from internal playtests, including adding new things specific to Swarm.

Dashboards: We spent significant time early on building dashboards to track this internal data in ways that were new to League but crucial for Swarm. Some examples of things that were new:

Average frame time based on game length: Since Swarm got more expensive as the game length increased (more enemies, more weapons, etc.), we needed to see where that curve was so we could project what the perf would be during that high engagement launch window.

Tracking average frame time per game per day: Normally, we track this patch to patch on live, but internally, things change every day. What this did was allow us to notice changes in frame time right away, which helped us track down what caused issues before it got lost in weeks’ worth of changes.

Per game counts of every type of object and how much frame time that type of object was taking: While we've always done this, it was usually at a higher, less detailed level—typically per patch. With Swarm, we needed to pinpoint exactly which games were causing our average frame times to rise or fall, so we could investigate further. For example, certain weapon combinations could significantly increase the time spent calculating missile trajectories, so we had to be able to drill down to the per-game, per-object level.

- Direct Access to Data: Historically, there wasn't a need for every engineer on a project to have access to the data directly. Instead, you would generally have engineers on project work with the data through the dashboards that were mentioned above. A big change for Swarm was giving every engineer on the team direct access to the data, which allowed us to use SQL queries to generate reports on anything we could think of. The time to make a good dashboard could be hours, whereas the time to query for something you only needed a couple times could be minutes. This empowered all the engineers on the team to quickly access any performance things they could think of.

Together this process led to the team being able to blow past our 80% performance target for PBE and actually ship closer to 60%, setting a new standard for how modes are made and showing that things like low player count PvE are possible.

Fun Fact: This process was later used by TFT in their development and release of Tocker’s Trials, a great example of how breaking ground for one mode can lead to success in future development.

PBE Launch

When it comes to capacity planning, a lot of the work is done before you even release. The release is about confirming that your planning was correct and mitigating emergent things that were missed. Swarm was no different in this regard, and we learned some very valuable things from the PBE release:

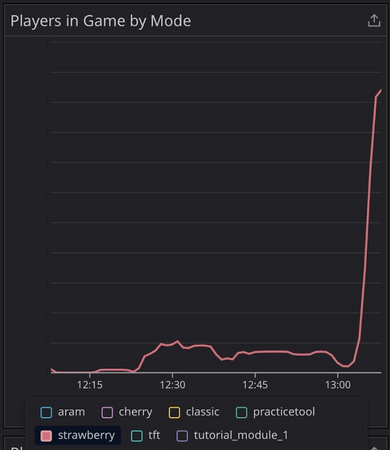

Engagement was higher than our projections: We saw about 8% higher engagement on PBE than we expected. This gave us a great indication for the live release and allowed us to set up mitigations–such as launching with queue timers–that helped make the live release extremely smooth.

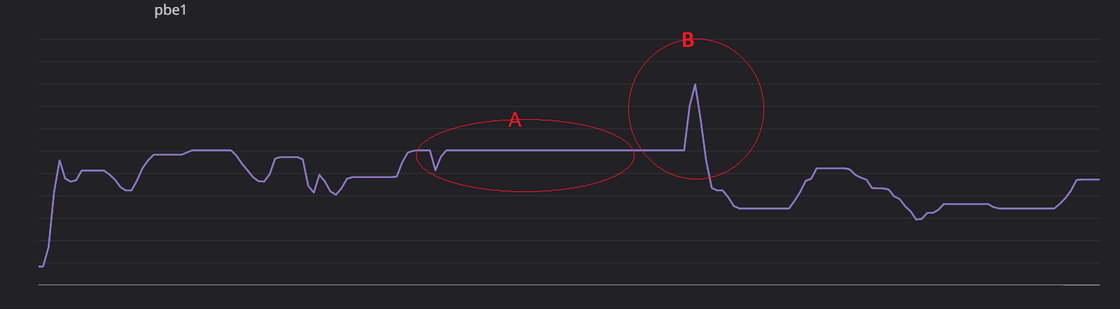

We were significantly off on our network bandwidth projections: Something unexpected was that we were using way more network bandwidth than we forecasted. When we did our projections, we used data from single player games only, which sent significantly less data than 2/3/4 player games. Since co-op games need to sync player state across all players, it is not linear scaling and four player games ended up costing around 8x more than of a single player game. Luckily for us, we had the capacity to absorb this; it just led to increased data center costs.

- Our limiting factor was not CPU load as projected: An interesting thing we found was that we optimized Swarm so much that we changed the location of the server bottleneck. Instead of it being how many games we can host before we run out of CPU or memory on a machine, it was actually how many games we can run on a machine before the network threads' overhead was maxed out. We had a limit of ~200 games per machine before we hit this limit, a limit we never got close to with Summoners Rift, as we would always hit CPU % limits before. Swarm was so well optimized that we hit this limit, causing even more scaling up than we expected.

Alerting was missing: Likely one of the most beneficial things we caught during our PBE run was that we were actually missing alerts for servers that would run into the max games limit. We had alerts for CPU, memory, and a host of other things, but since we had never run into this max games limit, it was something completely under the radar. Luckily, we caught it so we were able to get alerting on live, which helped us scale quicker.

We can't scale fast enough to handle the initial spike: It's known that new modes tend to have a strong initial engagement spike, and Swarm had an even more aggressive curve than normal. The way we handle auto scaling is we have a minimum number of instances, a max number of instances, and several triggers that cause another machine to be added to the pool. But so many players were coming in to play Swarm that we couldn't get new machines online and into the pool fast enough to handle the increases in load. On average, it takes 2-3 minutes for a new machine to be requested, spun up, and start accepting games, which proved to be too slow to handle the initial spike of players.

- Queue timers were extremely effective: With the higher than expected engagement, the limits on max games per machine, and the time it took to spin up, it gave us a chance to validate that queue timers (adding a delay from user hitting start game to getting a game server allocated) had the effect we expected. We found that adding a one minute queue timer reduced overall server load by ~15% and it also spread out the game starts in a way that mitigated the issue with the auto scaling being too slow to keep up.

Live Release

As launch day approached, we felt confident that we had an exceptionally solid plan in place. Over the course of about six months, at least ten engineers had contributed at various stages to prepare for this release, more than any game mode in recent memory. We spent months optimizing, setting up an environment we felt confident in, and implementing strong mitigations in high-risk areas. At that point, all that was left to do was activate worldwide and hope for the best.

A recap of all the major things we did in preparation:

Optimized as much as possible based on internal and PBE data: By the time we hit live, an average Swarm game cost ~58% less than an average game of Summoners Rift.

Scaled up based on projections: Based on original forecasts and PBE data we added over double our max server counts. Using a normal summer event as a baseline, we added 217% of the largest machines offered in addition to that baseline.

Inflated auto scaling lower limits to handle initial spike: In order to help handle the speed in which we could scale we started with ~75% of the machines active during the launch window, this increased our costs significantly during that time, but also helped ensure we wouldn't run into the limits of our autoscaling speed we saw on PBE.

Set up one minute queue timers from the start: Engineering and product teams combined to make the call that a one minute timer was the best thing to do for players. Since we knew that initial spike had the potential to bring down all of League, not just Swarm, we made the call to help reduce overall load by 15% to keep us in the green.

Overall, the regional activations were a success in terms of capacity planning. While we encountered a few hiccups due to routing issues between clients and our data centers, the measures we implemented largely hit the mark, resulting in minimal scaling issues.

Another major win was in managing costs. Our initial forecast projected expenses at around 2.5x the cost of a typical summer event. However, thanks to our optimization, careful planning, and mitigation efforts, we ended up closer to 1.5x the cost. At the scale of League of Legends, this is a huge achievement, demonstrating that we can technically deliver this type of mode in a sustainable way.

Conclusion

In the end, server capacity planning was crucial for both the modes team and League of Legends to ensure Swarm delivered the high-quality experience we expect for players. We gained support from all levels and teams, turning it into a successful, collaborative effort. Through this process, we learned valuable lessons and developed strategies that are already being used in future releases like Arena in 2025, setting us up for ongoing success.

Sending it over to Riot Regex to finish it out with a look at how existing systems were used to create Swarm’s roguelike progression system.

Around-Game Progression for Swarm

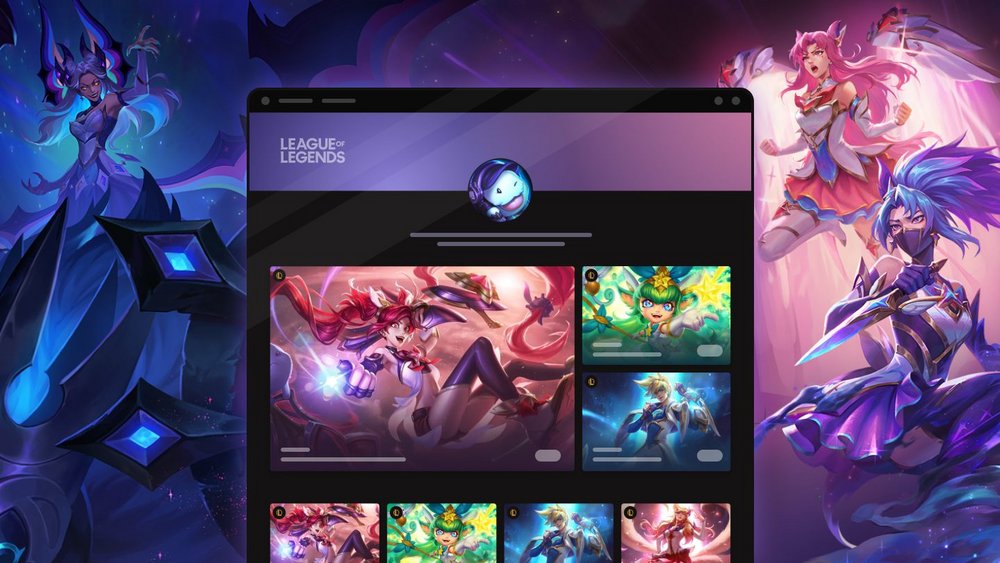

Hey there, folks–Riot Regex here! As a Software Engineer on Swarm, one of our core challenges was building an out-of-game progression system for a mode within a game that traditionally doesn’t support such systems. And we had to do it fast, without spinning up new services. Constraints often breed creativity, and we were able to stitch this system together using existing flows, primarily from our store and battlepass infrastructure.

Upgrades and Objectives

When we create a temporary mode like Swarm, we prioritize leveraging existing services, meaning we depend on other teams’ infrastructure. Ideally, we use these services out of the box, though we occasionally contribute strategic enhancements. These dependencies introduce constraints, but they also push us to get creative.

In Swarm, objectives were in-game actions that rewarded players with unlocks or gold used to purchase upgrades. These were powered by the same system as the Event Shop, itself backed by a Riot-wide progression platform maintained by our shared platform team. That platform typically handles small-scale progression: a handful of counters triggered by missions, granting one or two rewards daily per user.

For Swarm, we added 150 new counters with some updating once and others updating more frequently. A single game could increment between one and ten counters, granting up to ten rewards every 20 minutes. While the services supported our use cases, we invested significant time in capacity planning to avoid overwhelming them. Scaling was essential to handle our new data patterns.

We also added tooling to help designers author these counters, and we deployed the data using existing Event Shop pipelines. Without that foundation, we couldn’t have delivered as many objectives as we did.

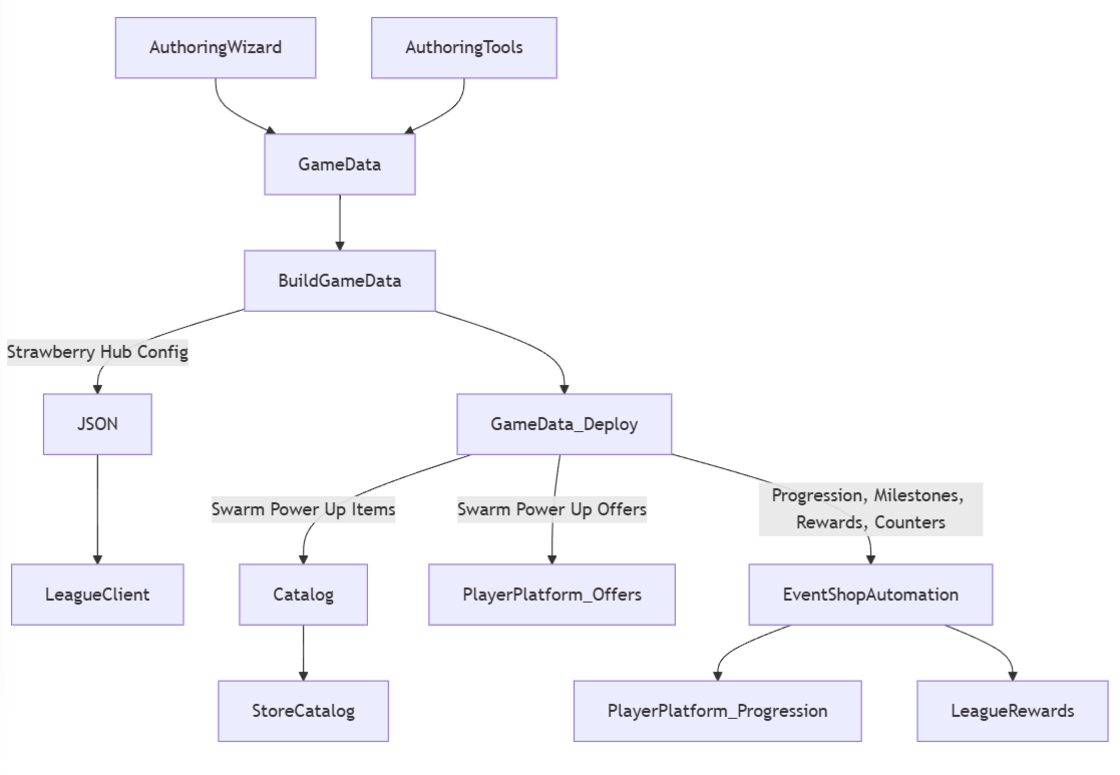

Authoring and Deploying Swarm Content

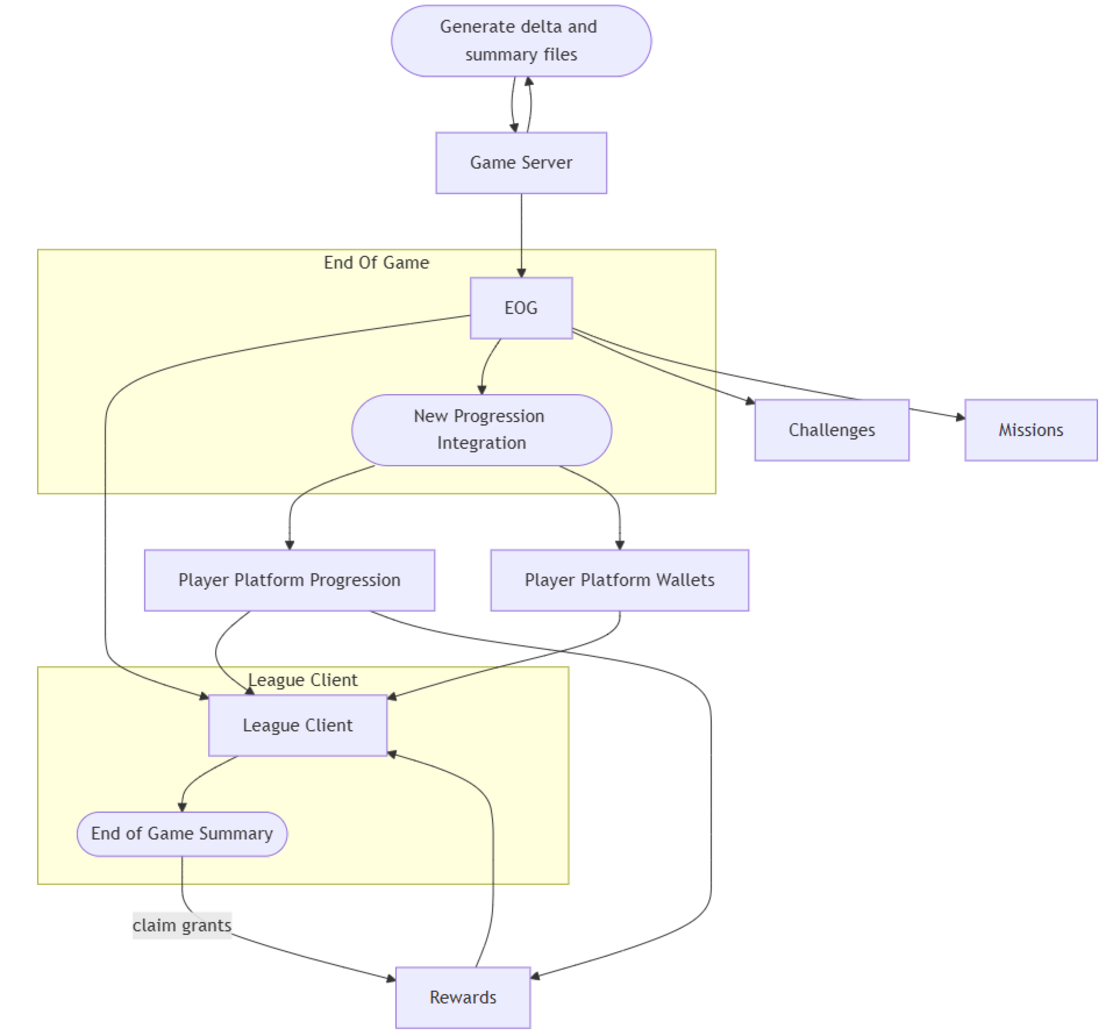

Most League progression systems are wired into specific stat output files from game servers. Adding a new stat often means updating multiple pipelines. To simplify, we introduced a generic progression integration. The game server emits a mapping file of Progression UUIDs to deltas, which we pick up at end-of-game and send to the progression service.

Why this roundabout flow? Game servers are intentionally isolated and don't contact other services. They must remain authoritative, avoiding external async dependencies. So we rely on output files instead.

We also enabled designers to hook progression directly into Lua Blocks, removing dev intervention. This gave designers more control, letting them define progression logic directly from gameplay. Since these systems run on raw UUIDs, we built lightweight tooling to ensure the data flowed smoothly across platforms. With these tools (even if half-baked), our around-game progression designer was able to work wonders.

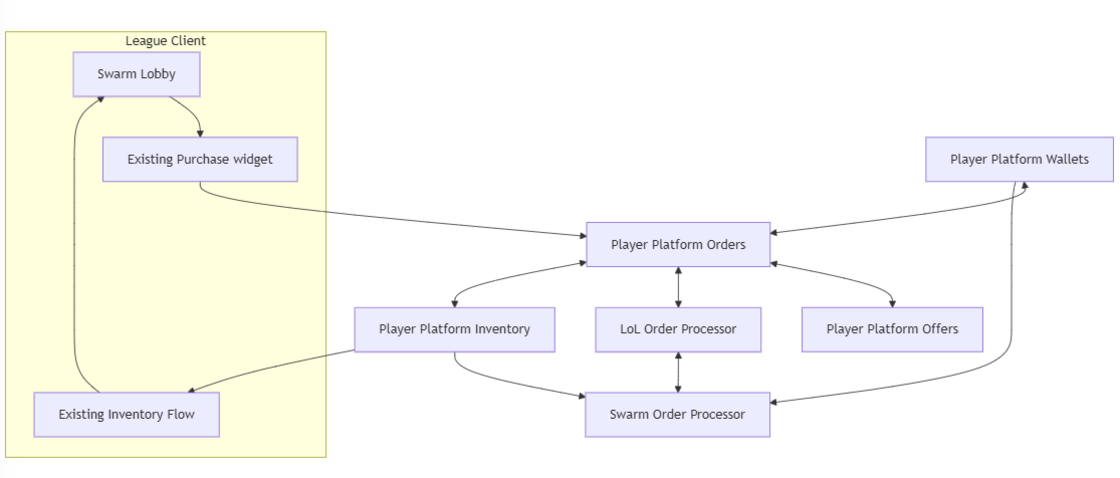

Upgrades formed the core of Swarm's “roguelike” experience. Players could choose power-ups that influenced their progression. Buying upgrades resembled a store transaction. However, the original League Store was designed when League was Riot’s only game, long before player platform unified our shared services across games. (If you’re wondering what player platform even is, check out this tech blog from a few years ago that goes in-depth on this team.)

While League has been transitioning to player platform support, it still depends on some of the original legacy store systems. For Swarm, we wanted the upgrade purchasing experience contained within the Swarm lobby, not mixed with the global store. Integrating with the old stack would have required complex configs and risked exposing items where they didn’t belong.

Instead, we followed the VALORANT model of interacting directly with player platform. We set up an offer for each upgrade and passed the offer ID to our orders system. Once it hits player platform, we still need to validate: does the player own it? Do they have enough currency? Since this logic is game-specific, we created a custom Swarm merchant service to process these offers. This was our biggest service contribution, enabling us to auto-export authored content and empower designers to iterate on pricing and items efficiently.

Anima Power was a late addition designed to extend gameplay depth. Our UI was initially built for about eight upgrades per category, and Anima Power had over 100. But, fortunately the same progress bar UI scaled well to accommodate this feature without needing an additional rework.

Connecting Around Game and In-Game Loop

Connecting Around-Game and In-Game Loops

Most Swarm lobby elements were built on well-known tech. Map and difficulty selection, for instance, used our loadout system, the same tech behind wards and emotes. It handles showing items in the client, assigning them to players, and loading them into the game. We simply set up existing patterns for low-cost integration.

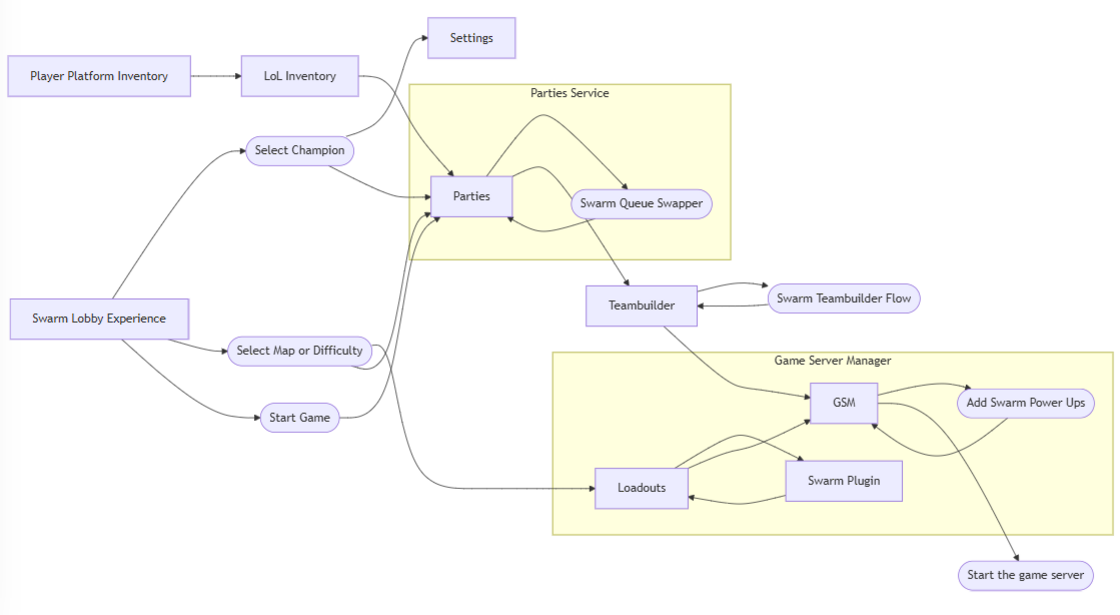

We did need custom service plugins for the "party leader only" behavior in loadouts. The game start flow begins in the parties service, hands off to teambuilder, and finally lands in game server manager. Our matchmaking system already supports plugins during queue, initially built for Arena’s 16-player non-ranked games. We extended this system for Swarm.

In the background, we have four separate queues based on party size. When players queued, they were routed directly to the queue matching their party. This gave us visibility into queue distribution and levers for performance tuning and matchmaking.

Swarm Boons and the Catalog

At the heart of Swarm’s progression is a new inventory type called “swarm boons,” which fuel the power-up system. League typically binds ownership to specific loadout slots (e.g., ward skins, emotes), but boons require sending everything a player owns into the game, not just assigned items.

Hall of Legends pioneered a similar system with skin augments which checked a player’s owned items and sent them into the match. We followed that pattern and expanded it for Swarm. Though boons used some loadout infrastructure, they didn’t offer player-selectable loadouts.

The trickiest part was getting our boons into the catalog—one of League’s oldest systems. For an item to exist across the League Client and services, it must exist in the catalog. We added automation to streamline this process, borrowing from TFT’s approach to auto-authoring cosmetics.

Conclusion

In software, progress often comes from building on the shoulders of others. The same is true at Riot. We repurposed foundational systems from League’s store and battlepass tech to create a compelling progression experience for Swarm.

While Swarm was delivered by a relatively small team, it wouldn’t have been possible without tremendous support from Riot’s internal platform teams. Huge thanks to everyone who contributed—and to the players who enjoyed their time with Swarm!

If you’re reading this you just read 6,500 words of the tech behind Swarm–or you skipped to the end–either way, good for you! If you’d like to read more technical deep dives like this one, check out the Riot Games Tech Blog for articles like Streamlining Server Selection and The Tech Behind Mel’s W.